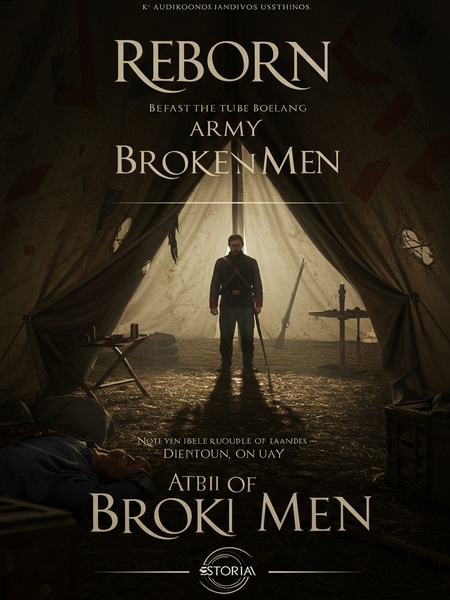

Chapter 3: The Birth of the Army of the Potomac

First, let’s talk about the founding of the Army of the Potomac.

Walk the fields at Arlington or along the Potomac and you’ll see monuments now, but back then, it was nothing but tension and uncertainty. Nobody knew who would win.

In 1861, after Fort Sumter fell, the country spun into chaos. The government was blindsided, betrayed, and scrambling. Congress became a battleground of shouting matches and wild ideas.

Newspapers in Washington shouted about traitors, and rumors crawled through the city like fog. In Congress, lawmakers fought as hard as the soldiers would soon fight in the field.

"The Founding of an Army" shows it well: some wanted to copy Europe, launching quick attacks, while Lincoln and his crew pushed for patience and strategy—betting the farm on citizen-soldiers.

Old generals, trained on Napoleonic charges, wanted one big blow to end it all. But Lincoln, with his rail-splitter grit, saw that the American way meant holding on, even when the odds looked bad.

Against all this, the government launched the First Battle of Bull Run and the Peninsula Campaign. The enemy was stronger than anyone guessed, and both ended in disaster.

Bull Run became a cautionary tale—soldiers and sightseers running for their lives. The Peninsula Campaign promised glory, but brought only mud, fever, and heartbreak.

After McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign went sideways, he took stock, gave up the dream of taking Richmond right away, and pulled his battered troops to Harrison’s Landing in July 1862. There, they finally caught their breath.

At Harrison’s Landing, tired men set up camp along the James River. For many, it was the first time in months they felt hope. McClellan’s steady hand calmed nerves, even if it meant shelving big plans for a while.

With Harrison’s Landing as a base, Lincoln set up his fateful meeting with Grant. But how did Grant arrive?

That meeting wasn’t just a footnote—it was a turning point. Lincoln saw in Grant something more than just a good officer—a toughness that wouldn’t break, no matter what.

Grant’s place in history is tied to this moment. Understanding how he got there shows just how rare his brand of stubbornness was.

The Western campaign’s backbone was Sherman and Thomas’s men. At first, Grant wasn’t front and center. But when the Union retreat south turned ugly, with Confederate forces hot on their heels, Grant led 3,000 men at Shiloh to hold off the enemy and buy time.

Picture the chaos: smoke so thick you could choke on it, gunfire echoing through Tennessee woods. Grant, quiet as always, faced the impossible without blinking—his men digging in, knowing it might be the end.

Grant was staring down a suicide mission, facing 20,000 under Johnston. He knew the odds, but didn’t flinch.

He didn’t waste words—just set his jaw, gave his orders, and got to work. That resolve spread, steady as a heartbeat.

The upshot? The main southern force was nearly wiped out at Corinth. Sherman and Thomas broke out and regrouped, others made for Washington or just went home.

Survivors remember stumbling through swamps, patching wounds with whatever they had left. But those who regrouped under Sherman and Thomas became the core of the army’s next push.

The campaign failed, leaders scattered, and nobody knew what to do next.

Sometimes, war feels like a fog you can’t see through. Even the best were left wondering if it was all over.

Grant, holding the line at Shiloh, was outnumbered and had to break out, too. By then, morale was shot. Folks muttered, “The main force is gone—why stick around?”

Campfires burned low. Some wept, others just packed up, ready to walk away. The air was thick with despair.

As the days dragged on, fewer men stayed. By late July, all the division and brigade commanders and staff had left—except Grant at division, and Rawlins and Logan at brigade. The unit was hanging by a thread.

Those who stayed were the stubborn kind—tough as boot leather. The smaller Grant’s circle got, the more determined he became.

At that breaking point, Grant’s faith in the cause burned brighter. He called the remaining officers and men together, asking: Who’s willing to keep going?

His speech wasn’t fancy—just honest: “If we have to start over, then we start over. But we keep moving, for the Union.” Some men wiped their eyes on their sleeves, others just nodded, jaws set. Nobody wanted to be the first to walk away.

With just 800 left, Grant led them through hardship and heartbreak to Tennessee, finally linking up with Lincoln’s forces. Among the few sparks he kept alive were Sherman, then a colonel; Sheridan, a captain; and Logan, the brigade chief.

They slogged through rain and mud, hungry but hopeful. No one knew what history had in store—but they marched anyway, believing in something bigger than themselves.

Who could have guessed these ordinary men would go on to command Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Atlanta, becoming Civil War legends?

Today, statues and street names honor them, but back then, they were just survivors—proof that greatness starts with refusing to quit.

Another thing: Grant’s regulars fought differently than the old Tennessee volunteers. Because he went to Tennessee, the base held out against repeated attacks.

Historians note that Grant’s drilling and discipline quickly turned a ragtag force into a unit that could stand up to the best. It’s still studied at the Army War College.

General Thomas later said if Grant hadn’t gone to Tennessee, the Peninsula Campaign troops alone wouldn’t have made it.

Thomas’s memoirs call Grant’s decision the lynchpin of the western strategy. Sometimes, one leader’s choice is all that stands between victory and disaster.

Grant, in the darkest times, kept the Union flame alive. That’s why he’s called the father of the modern U.S. Army.

Every Memorial Day, there’s a wreath on Grant’s Tomb. It’s more than tradition—it’s a quiet nod to the power of stubborn hope.

In July 1862, Grant led his men to Tennessee, joined up with Lincoln, and, on orders from the War Department, formed the Army of the Potomac.

Official records from that summer are short, but you can read the relief between the lines. Finally, a force to trust. Soldiers wrote home with hope again.

When the armies joined up, everyone cheered. But new headaches popped up fast.

It was like trying to win the Super Bowl with a roster pulled from three different high school teams—talented, sure, but no one spoke the same playbook.

At that time, the Army of the Potomac was mainly three groups:

Even now, history buffs argue about who was best—each group with its own pride, grudges, and memories of old slights.

First: Lincoln’s Peninsula Campaign volunteers, reorganized as the 31st Regiment, plus Virginia volunteers who became the 29th and 30th (later disbanded).

These were small-town boys, new to soldiering. They learned the hard way what real battle meant.

Second: Grant and Rawlins’s Shiloh regulars—the 28th Regiment.

Hardened by loss, these regulars were the backbone, setting the bar for everyone else.

Third: The Tennessee team, reorganized into the 32nd Regiment.

These guys, fiercely loyal, knew the land and how to dig in.

The force was diverse—different skills, mindsets, and attitudes. Tension was baked in from day one.

Anyone who’s joined a new varsity team or big family reunion knows how fast friction can flare. Leaders had to manage not just tactics, but bruised egos and old wounds.

In battle, the 28th Regiment—Grant’s regulars—were the gold standard. They’d been drilled and tested, worlds apart from the fresh-faced volunteers.

On the parade ground, the difference was clear: the 28th marched like clockwork; the rest, not so much. Leadership had to close the gap, and fast.

So, generally, when there was a battle, the combat arrangement was as follows:

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters