Chapter 2: The Union Army—From Ragtag to Resilient

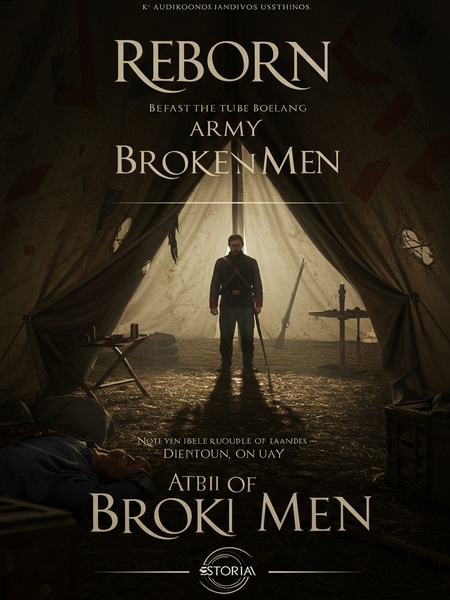

Funny enough, I caught an old movie the other night—"The Bugle at Gettysburg." It tells the story of how the Union Army was born during the Civil War, laying the groundwork for today’s U.S. Army. Let’s use that as our jumping-off point to figure out what made the American army so tough.

The black-and-white images flickered on my screen, but the message was loud and clear: this was about transformation. Not just of soldiers, but of the very idea of America. The Union Army didn’t just march—they carried a cause on their shoulders.

The biggest difference between the Union Army and the old militias? These troops were armed with something stronger than bullets: ideology.

You can see it in the letters they sent home—quoting Lincoln, wrestling with the meaning of freedom. One fictional letter comes to mind: “Ma, I’m not just fighting for pay—I’m fighting so my little brother grows up free.” For these kids, it wasn’t just about the money. It was about believing they could change the world.

And that’s the heart of it: why become a soldier?

From Kentucky hollers to Boston’s cobblestones, that question hung heavy. Why risk everything? Why leave family, fields, or the local shop for the gamble of war?

In the old militias, it was just a paycheck or a way to dodge the draft. But who would risk their life for a few bucks? No surprise—when things got rough, a lot of those guys would slip out the back, boots crunching on frosty grass, hoping nobody noticed.

A lot of those militia men—farmers, tradesmen, immigrants with nothing but a dream—saw soldiering as a last-ditch gig. When bullets flew and hope faded, plenty figured it was time to get gone, back to whatever life they could salvage.

But in the Union Army, wearing the uniform meant taking the cause—ending slavery, saving the nation—as your own. Sacrifice wasn’t just expected, it was honored. The result? Even if a company was scattered, just two or three soldiers could rally, find each other, and hold the line.

That new sense of purpose ran deep. Soldiers scribbled in diaries about fighting for "the Union," for "liberty," for "the kids yet to come." Even in chaos, little knots of men would find each other, stubborn as the old stone walls they used for cover.

The difference in combat effectiveness was plain as day.

Modern military instructors still point back to the Civil War: when an army believes in something bigger than itself, it fights different—harder, longer, and with more heart. That lesson echoes in every American war since.

But let’s be real: the Union Army didn’t start off as a band of heroes.

At first, the Union Army was a patchwork quilt—soldiers bickering over chow, officers at odds, everyone figuring it out as they went. Ideals take root slow, usually in the mud, not the parade ground.

You can’t expect folks to become patriots overnight just because they get handed a uniform. That kind of transformation is a grind—a journey, not a lightning strike.

Truth is, the first Union Army was a wild mix: state militias, eager immigrants, and even outlaws like Jesse Evans and Cole Younger.

There were Irish immigrants with brogues thick as stew, Black soldiers with hymns on their lips, and Missouri farm boys who’d never seen a city. Some had rap sheets, others had nothing but calloused hands and hope.

Could a ragtag bunch like that become unstoppable just because someone said so? Not a chance.

Anyone who’s tried to build a winning team knows you can’t just throw people together and call it good. Trust, grit, and discipline have to be earned.

What changed everything was leadership—hard-nosed, stubborn, and relentless—and a steady drumbeat of teaching and transformation.

It took drilling until your arms ached, speeches that made you choke up, and leaders who stuck it out through thick and thin. Officers became mentors; chaplains, confidants; and campfires, classrooms for fierce debates.

Lincoln and his generals shook things up, building clear command structures down to the company level. It was a game-changer, but only reformed the scraps left from the early volunteers.

Lincoln’s insistence on civilian control of the military? That was a tough sell. It sparked fierce fights and left him standing alone more than once.

Historians still talk about Lincoln burning the midnight oil, reading reports while his own cabinet and the press hammered him. He stood his ground, even as generals bristled, sure civilian control would tie their hands.

Everything shifted with the Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863. “Government of the people, by the people, for the people”—that was the spark. Veterans said Lincoln’s words made their hair stand on end. The speech didn’t just mourn the dead—it gave the living a reason to keep fighting.

Let’s zoom in on that stretch of history.

This chapter isn’t just battle lists. It’s chaos, doubt, and transformation—played out in muddy camps, smoky war rooms, and letters home.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters