Chapter 3: The Interview

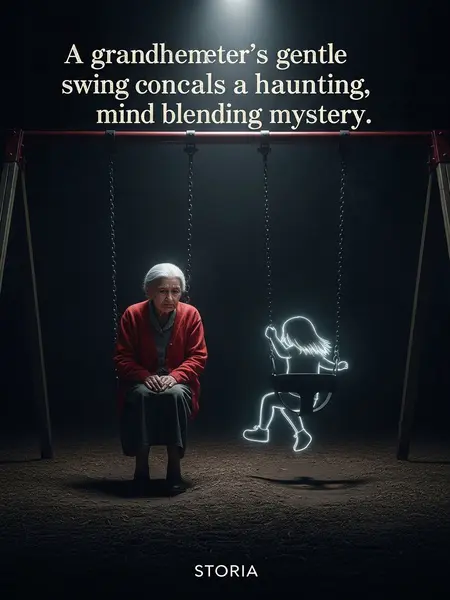

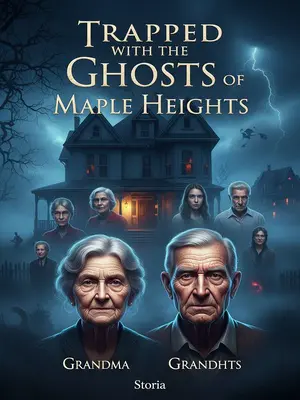

The identity of the deceased was confirmed. Her name was Madison Lee, ten years old, the old woman's granddaughter.

The paperwork was stark and clinical: Madison Lee. Age ten. Next of kin: George Lee and Carol Lee. A little girl whose favorite place, according to the principal, had always been the swings at recess. My heart sank as I read her name out loud, another file in a system that could never explain this kind of loss.

The exact cause of death still needed to be determined by the medical examiner.

The coroner’s van had left the playground an hour before dawn, taillights swallowed by the mist. We all waited for Dr. Wilson’s report, knowing that whatever it said, it wouldn’t make the truth any easier to live with.

I asked the old woman to tell us what happened. She said,

She sat in the fluorescent-lit interview room, hands trembling around a Styrofoam cup of lukewarm coffee. A Red Sox mug sat untouched at the edge of the table, left behind by the last shift. Her eyes darted between me and Ramirez, searching for something familiar. She swallowed hard, then spoke.

"This evening, I brought my granddaughter here to play on the swings. We’d only been here a little while before you all showed up."

Her voice was quiet, barely more than a whisper, as if she were afraid of waking a sleeping house. She looked down at her lap, twisting a tissue between her hands until it was shredded.

At this point, her face was full of sorrow, and two cloudy tears rolled down her cheeks.

She dabbed at her face with the back of her hand, leaving faint streaks on her cheeks. For a moment, she seemed smaller, lost in her grief—an old woman drowning in the weight of what had happened.

"How did my granddaughter die all of a sudden?"

The words cracked. I could see the fear and guilt twisting behind her eyes. She looked up at me, silently begging for an answer I didn’t have.

I watched her closely. She didn’t seem to be lying.

There was nothing calculating in her expression—just the raw, bewildered pain of someone who had lost her anchor. Ramirez leaned forward, her voice gentle as she offered Carol a fresh cup of coffee.

But what she called 'a little while' had actually been nearly six hours.

I checked my notes, comparing the timeline. We’d gotten the call at midnight, but the witness said they’d seen her and Madison swinging before dinner—around six. The math didn’t add up. My brow furrowed. Something about time had slipped for Carol Lee.

I thought to myself, the old woman in front of me was probably not mentally well.

She drifted in and out, sometimes talking about Madison’s last birthday, sometimes asking what time it was, as if the clock had stopped working for her. I’d seen it before—memory loss that came and went, days blending together until even the most familiar faces seemed like strangers. The ache in my chest deepened.

To confirm, I asked,

"Do you realize your granddaughter was on the swing for almost six hours?"

My voice was as gentle as I could make it, careful not to spook her further. I watched her reaction, searching for any flicker of recognition.

Sure enough, she looked startled.

She blinked rapidly, her jaw working. "What? That can’t be."

"What are you talking about? We only played for half an hour."

She insisted, her voice trembling. The denial was so complete, so genuine, that it sent a chill through me. I made a note to request a full medical evaluation.

A bold theory formed in my mind: the old woman might have amnesia.

I scribbled in my notepad, thinking back to cases I’d read about—how people could get caught in a loop, reliving the same moment over and over. Had Carol’s mind trapped her in those last happy seconds, refusing to let her see what was really happening?

She lost track of time and kept pushing her granddaughter on the swing, over and over.

The image haunted me—a grandmother so lost she didn’t even realize her granddaughter was gone. I glanced at Ramirez, who nodded, sharing my worry. None of us spoke; there was nothing to say.

Until the granddaughter sensed something was wrong and tried to get her grandma to stop—but Grandma didn’t respond at all. The little girl was scared to death on the swing.

My throat tightened as I imagined it: Madison’s growing fear, her calls for help lost in the darkness, her grandma unreachable. No child should ever have to feel that alone. I pressed my hand to my chest, steadying my breathing.

According to the caller, he went out for a walk after dinner at six and saw the old woman and the girl on the swing, even hearing the girl laugh happily.

The man had been matter-of-fact on the phone, but there was an undercurrent of guilt in his voice when I interviewed him in person. "They looked fine to me," he’d said, shaking his head. "Just two folks having a good time. Didn’t think twice about it."

That meant the girl was still alive at that time.

I scribbled a note in the margin—Alive at 6pm. We still didn’t know exactly when everything went so wrong, but at least we had a starting point. The timeline was tightening.

When he returned at seven, they were still playing, but he didn’t think much of it.

"Yeah, saw 'em again," he’d told me. "Still swinging, still laughing. I figured maybe they lost track of time. Kids get caught up in playing, you know?" He gave a helpless shrug, as if trying to convince himself it could’ve been anyone’s family.

It wasn’t until midnight, when he went out to buy cigarettes, that he saw the two of them still swinging.

He described the scene in hushed tones, like someone recounting a ghost story around a campfire. "I swear, officer, it was like the whole world had gone still. Not a sound—just the squeak of that swing. That’s when I knew something was wrong."

By then, it was late and there was no more laughter.

He paused, his hands trembling as he mimed lighting a cigarette. "That little girl wasn’t laughing anymore. She was just… there. Like a doll. The hair on my arms stood up."

That part of the neighborhood was pretty empty at night.

The playground sat in a little hollow between the old school and a row of shuttered stores. No cars, no kids, not even the stray dogs that sometimes prowled the alleys. The silence felt heavy—unnatural.

The scene started to feel horrifying, and he couldn’t take it anymore.

He’d admitted, voice cracking, "I had to get outta there. Just bolted home and called you all. My wife thought I was seeing things. I just… I couldn’t leave them out there alone."

Terrified, he hurried home and called 911.

Even after we’d thanked him, he lingered on the porch, arms wrapped tight around himself, as if afraid the shadows might reach up and pull him under. I made a note to check on him later—these calls left scars on everyone, not just the families involved.

Just then, Madison's father, George Lee, arrived at the station.

He came in looking like he’d been dragged through hell—rumpled clothes, haunted eyes. He clutched a battered ballcap in one hand, the other trembling as he wiped his nose. Ramirez offered him a chair, but he just hovered near the door, unable to settle.

He looked like an honest, tired middle-aged man, his eyes red and swollen, like he’d already cried.

He stared at the floor, voice thick. There was a heaviness in the way he carried himself, as if the whole world had landed on his shoulders all at once. A line of stubble shadowed his jaw, and his boots were scuffed and muddy.

He spoke in a dull, flat tone:

"Officer, this was an accident. My mom will be all right, won’t she?"

His voice was hoarse, barely more than a whisper. He glanced up, searching my face for reassurance I couldn’t give. The hope in his eyes was already flickering out.

Before I could say more, he handed over a doctor’s note.

He slid the paper across the desk, hands shaking. It was a letterhead from the county hospital, scrawled with notes about Carol Lee’s memory lapses. I scanned it quickly—intermittent amnesia, possible early-stage dementia. It all made an awful kind of sense.

It showed that Madison’s grandmother, Carol Lee, suffered from intermittent amnesia.

I nodded, offering the note to Ramirez, who read it and sighed. "Thank you, Mr. Lee. We’ll keep this on file."

Just as I’d guessed—this was most likely a tragic accident.

I tried to keep my voice even, but my hands clenched around my notepad. Accidents happen, but this one felt like it had been written in the shadows—avoidable, maybe, but not by anyone in that playground.

But for the old woman, knowing her granddaughter had died like this—how could she ever bear it?

I watched Carol through the glass wall, head bowed, shoulders trembling. It was the kind of grief that would haunt a person for the rest of their life. I wondered if her mind would ever let her remember—or if this mercy, small as it was, would be all she had left.

George said his daughter had a congenital heart condition and couldn’t handle too much shock.

He explained quietly, rubbing his hands together. "The doctors said to keep her calm, no surprises, no roughhousing. We tried, but…" His voice trailed off, and he bit back a fresh wave of tears.

I asked, "It was the middle of the night and your mom and daughter hadn’t come home. Why didn’t you go look for them?"

I tried not to sound accusatory, but the words came out sharper than I intended. Ramirez shot me a warning glance, but I couldn’t help it—there was a missing piece, and I needed to know.

His eyes darted away and he stammered:

"I was out drinking with friends… It’s all my fault, I drink too much."

His confession tumbled out in a rush. He squeezed his eyes shut, pressing the heel of his hand to his forehead, as if he could scrub away his guilt.

As he spoke, he slapped himself twice across the face, full of regret.

The sound was sharp in the quiet office. "I screwed up. I always screw up. Damn it." His face flushed with shame, and he wouldn’t meet my eyes. Ramirez stepped in, placing a gentle hand on his arm, murmuring words of comfort.

Even before I got close, I could smell the booze on him. I sighed. What an unfit father.

The odor of whiskey clung to him like a second skin. My disappointment must have shown on my face, because he flinched, looking smaller somehow. I wondered what Madison’s life had been like at home, how much she’d had to fend for herself.

The girl’s mother was working out of state.

George’s voice was flat. "She’s in Indiana. Hasn’t been home since the holidays. Work’s hard to come by these days." He wiped his nose, swallowing the rest of his words.