Chapter 4: The Rise and Fall of the Black Hawk Band

The Progressive Era, with Roosevelt at the helm, brought new, more open policies for non-mainstream peoples. With this spirit, the highly autonomous tribal government system was developed, building on the old 19th-century reservation model.

(Note: Reservation and tribal systems weren’t the same. On reservations, native leaders were mostly self-appointed and only had to report to Washington once in a while—just enough to keep up appearances. But under the tribal system, leaders had to be formally recognized by the feds and pay taxes, send men for military service, and play by D.C.’s rules.)

The distinctions mattered—not just to bureaucrats in D.C., but to ordinary folks on the ground. What seemed like hair-splitting legalese in the capital was a matter of life or death in small-town Iowa or the Nebraska plains.

After the Progressive Era reforms, federal agents were dispatched throughout the country as the highest local administrative officials. In mainstream areas, the agents managed government offices, while in minority regions, the federal government appointed local leaders as tribal officials under the supervision of the agents.

The arrival of a federal agent was a major event in small communities—part sheriff, part social worker, part judge. Kids would whisper about the "government man" riding into town, and adults eyed him with a wary mix of hope and suspicion.

Records show that nearly 300 tribal institutions of all sizes sprang up nationwide. This was a big step up from the old reservation system, letting Washington call the shots from afar. But in exchange, D.C. gave up a lot of its hands-on control, letting the tribes run things their way—so long as they stayed loyal.

It was a messy compromise. On paper, it looked neat; in practice, it was a constant tug-of-war between local pride and federal authority.

The tribal system did cut down on open rebellion for a while, letting Washington focus on hotspots elsewhere. For a moment, it seemed like peace might finally stick.

After the Civil War, President Grant saw firsthand how the tribal system brought local stability. He was a practical man—willing to bend the rules to keep the peace.

Grant, ever the battlefield tactician, saw the value in compromise. He was no stranger to making hard calls and was willing to bend the rules if it meant keeping the peace—at least for a time.

Grant, rising from humble roots, abandoned the old doctrine of strict separation and made the tribal system a key tool for ruling minority areas. It nearly solved the "frontier threat" for a generation, letting families settle further west and railroads cut new lines with confidence.

But nothing lasts forever in America. Change always comes—sometimes in a flood.

Cracks began to show. Old grudges resurfaced, new leaders chafed against outside control, and what had once been a smart fix started looking more and more like a problem.

The system’s flaw was obvious: over time, the tribal regimes would get too strong, start thinking they didn’t need Washington anymore. Suddenly, yesterday’s partners were today’s threats.

The first tribe to break ranks after the Civil War was the Black Hawk band—famous across the Midwest, the stuff of schoolyard legends and dime novels.

They’d ruled for over 80 years, their territory stretching across a third of Iowa and parts of Illinois. Along with the Sioux Nation, they were the powerhouse of the Midwest—"Black Hawk and Sioux," folks called them, with a mix of fear and respect.

Faced with such a strong tribe, complete with its own private army, the government had few options but to try to win them over. As long as they remained loyal and refrained from rebellion, Washington would not interfere excessively.

It was a classic case of "don’t poke the bear"—let sleeping dogs lie, and maybe, just maybe, everyone could get along. At least until someone got greedy.

But that leniency went too far. The Black Hawk band, sensing weakness, started pushing back.

In 1876, Chief Black Hawk, the band’s leader, ignored federal law and, using a dispute over mineral rights as a pretext, teamed up with Chief Red Cloud to launch a private attack on a rival band. Locals called it the "Battle of the Ravine."

The night was chaos—gunshots echoing across the valleys, smoke curling over the treetops. The story would be retold at county fairs for generations.

As recorded in the American Annals: "Red Cloud thus conspired with Black Hawk against their rivals, raising troops. Black Hawk declared himself Supreme Chief, appointed Red Cloud as general, and led forces to attack the rival band."

Old-timers still whispered that the whole thing started over a card game gone bad, but official records paint a more calculated picture: two ambitious men, hungry for power, willing to risk everything.

They won. Black Hawk invaded, desecrated burial grounds, and killed the rival chief’s brother. The rival chief fled with his family and begged Washington for help.

Neighbors took sides, friendships frayed, and by the end of it, the sense of community had been shredded. The rival chief’s desperate plea to Washington was a Hail Mary pass—a final bid for order from a higher power.

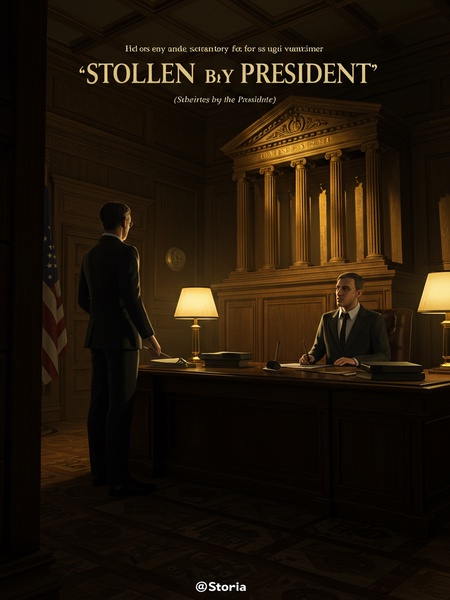

President Grant summoned Black Hawk and Red Cloud to Washington. Not only did they refuse, they doubled down—preparing for war and openly defying the feds.

In today’s terms, they were like small-town bosses thumbing their noses at the FBI—brazen, reckless, certain they were untouchable.

Black Hawk’s actions bordered on madness.

Folks in Washington muttered about "going off the deep end." Even his own allies started to edge away, worried that he’d finally gone too far.

But who was Ulysses S. Grant? He was the most formidable general of his era. Black Hawk’s defiance was like brandishing a pocketknife in front of General Patton—a pointless display.

The White House, always bustling with telegrams and military maps, braced for the showdown. If there was one thing Grant knew, it was how to finish a fight.

In 1878, the president ordered General Sherman to lead 50,000 troops to suppress the rebellion.

The order went out over crackling telegraph lines, and within weeks, troop trains rolled west, boots thumping on the prairie soil. Locals watched from front porches, the air thick with a sense of inevitable reckoning.

The outcome was predictable: the tribal forces were routed in their first engagement. Black Hawk and Red Cloud were captured and sent to the capital for punishment.

It was all over but the shouting. In the end, might made right—at least for that moment in history. The defeated leaders were paraded through the capital, a cautionary tale for would-be rebels.

According to the usual script, the rival chief should next have knelt before the president, expressed gratitude for the government’s justice, and then returned in glory to resume his position as leader.

Political theater at its finest—everyone expected the photo op, the handshake, the triumphant homecoming.

The president and his cabinet initially thought so as well. Having demonstrated federal might, allowing the rival chief to resume his post would display the government’s benevolence.

Advisors planned the press release, and the D.C. rumor mill kicked into overdrive. People speculated about who’d get which post, whose fortunes would rise, and whose would fall.

However, an unexpected development made Grant reconsider.

A single whispered accusation, carried across a marble-tiled corridor, changed everything. The White House buzzed with intrigue, aides scurrying from one office to another.

When Black Hawk was brought to Washington, Grant ordered the rival chief to confront him. During this meeting, the rival chief made a shocking accusation: he claimed that Black Hawk and Red Cloud’s attack was motivated by Red Cloud’s illicit affair with his (the rival chief’s) grandmother. Upon hearing this, the grandmother, enraged, exposed an even greater scandal: the rival chief was violent and lawless, having strangled his own mother—an unpardonable crime.

In a scene that would have fit right into the tabloids, family secrets spilled out under the gaze of the nation’s highest officials. You could feel the room freeze—politicians shifting in their chairs, the weight of scandal settling like dust.

Stunned by this revelation, the president and his cabinet realized that the chaos among the tribes far exceeded their expectations.

You could almost hear the collective intake of breath—a nation’s dirty laundry aired at the highest level. It was a political mess with no easy fix.

Clearly, neither Black Hawk’s rebellion nor the rival chief’s crime of matricide could be forgiven. To pardon them would undermine the government’s credibility.

There was no way to spin this for the evening papers. Grant knew that letting either man off would look like weakness—a risk he couldn’t take.

After careful deliberation, Grant decided to abolish the tribal offices in the region, establish counties in their place, and set up the Iowa State Administration, bringing the region under direct federal control.

New county lines were drawn, courthouse steps swept clean, and for the first time, the people of Iowa found themselves answering directly to the federal government. It was a seismic shift—the kind that redefines a region for generations.

Thus began the government’s abolition of the tribal system and the establishment of Iowa as a state.

The change didn’t happen overnight. There were protests, letters to the editor, and more than a few tense town hall meetings. But by the end, the old system was gone—its memory preserved only in family stories and the names of a few back roads.

The old order was gone, but nobody could say what would rise from its ashes.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters