Chapter 3: Milk and Blood Money

A few days later, while I was picking up groceries at Walmart, Mark’s mother, Carol Jennings, stopped me.

It was a muggy Saturday—the kind where the AC barely kept up. Carol found me by the Redbox, eyes red-rimmed, voice trembling. She clutched a battered envelope and a lukewarm case of Horizon milk like they were life preservers.

Shaking, she pressed five thousand dollars and the milk into my hands, begging me to spare her son and not let Mark go to jail.

Her voice was barely more than a whisper, desperate but polite. Shoppers glanced over, some pausing, but I didn’t care—I just felt sad.

As a bus driver, Mark earned less than $2,000 a month, most going to his mother’s medical bills. This five grand was all she had.

I’d heard about her garage sales—old records, a ‘90s toaster oven. This was everything she had left.

I gently pushed the money and milk back. "Instead of giving me money, you should hire a good lawyer for Mark. That’ll help your son more."

I tried to sound firm, not unkind. She looked at me, eyes brimming, and nodded, hugging the envelope tighter.

Carol shook her head. She wasn’t here for a letter of forgiveness. She wanted my daughter to recant her testimony.

She struggled to get the words out, her voice cracking. For a moment, I felt the weight she was carrying. The parking lot shimmered in the heat.

"My son would never hurt your daughter, please believe me. That’s because..."

She trailed off, her mouth working, as if she wanted to reveal something but couldn’t. Her hands twisted her purse handles, knuckles white.

Carol hesitated, her face twisted with pain, as if she had something she just couldn’t say.

I wondered if she was afraid or hiding a secret that might change everything. I wanted to comfort her, but I also wanted to escape.

Growing impatient, I pushed the money and milk back. "You should really get a good lawyer."

My voice was sharper than I meant. She flinched, stepping back, the envelope nearly slipping from her hands. I felt guilty, but didn’t know how to fix it.

Maybe my words worked, because not long after, I got a letter from a law office. The sender claimed to be Mark’s defense attorney and would plead not guilty at the second trial.

The letter came in a plain white envelope, official letterhead and all. My wife read it over my shoulder, brow furrowing as she scanned the lines.

The lawyer even stressed: "If we win, we will pursue your daughter’s legal responsibility, and as her guardian, you will also be held accountable."

It sounded threatening, but not unexpected. The letter’s tone was stiff, almost theatrical—like it was written more for effect than substance.

I just laughed it off. I’m a lawyer myself, and honestly, this kind of letter is like a kid’s threat.

Still, I made a mental note to double-check legal angles, just in case. Old habits die hard.

But the other parents were different. They were really worried about being sued, and the group chat blew up.

By noon, my phone buzzed non-stop—worried emojis, frantic messages, half-baked legal theories. Some parents started talking about hiring their own lawyers.

They kept tagging me, asking what to do. I answered honestly: "It’s almost impossible to overturn a case on appeal. Since the other side isn’t looking for a settlement but is pleading not guilty, they probably have strong evidence in Mark’s favor."

I tried to sound reassuring, but it only made them more anxious. My wife muttered about how group chats always made things worse.

Maybe my words made them even more anxious. A few weeks later, I saw a trending topic—"School Bus Driver Molestation Case About to Go to Trial: Who Will Stand Up for the Girls?"

It was everywhere—local news, Facebook, even the neighborhood Nextdoor. I clicked on the hashtag, bracing for the worst.

There was a video—five girls, including my daughter, looking innocent and sweet. At the end, a photo of Mark lying under the bus, changing oil—dirty and exhausted.

The video was slick, cut to tug at the heartstrings. The girls looked like angels, Mark looked almost grotesque—unshaven, sweat-stained, nothing like the man I remembered.

The video’s intent was obvious, and it worked. The comments were brutal—people cursing Mark, calling him a monster, demanding the harshest punishment.

Scrolling through, I saw neighbors and strangers piling on. Some comments were so cruel, I had to stop reading. My wife insisted we keep a low profile for a while.

For a while, the “school bus driver molestation case” became known citywide. The first to panic were other parents, because Mark had driven the bus for ten years. No one knew how many kids he’d driven. Many parents worried their daughters might have been victims, too.

Rumors swirled in PTA meetings, at Little League, even in the checkout line. Some parents grilled their kids; others started driving them themselves.

Friends and relatives, hearing my daughter had been molested, all came to comfort me. It made me really uncomfortable.

Relatives dropped off casseroles; church ladies left voicemails offering prayers. I felt more isolated than ever, wishing the world would just move on.

Due to public pressure, the court decided to handle things quietly, and the second trial date kept getting postponed.

Weeks stretched into months. Every time the phone rang, my heart jumped. My wife started sleeping with her phone on silent, just for peace of mind.

But the one under the most pressure was Mark’s mother, Carol Jennings. All the parents who suspected their kids had been molested went to Carol for answers. When she refused to come out, they threw garbage and paint on her house.

Her little white bungalow became a neighborhood pariah. The siding was stained and the lawn overrun. I saw it in passing, my stomach twisting at the sight.

Even if she managed to sneak out, she was like a pariah—no one would sell her anything. Even at the hospital, doctors and nurses treated her coldly.

She had nowhere left to turn. I overheard neighbors say the grocery store started ignoring her. The pharmacist avoided her eyes. The isolation was total, merciless.

No one can withstand that kind of pressure. Not long after, Carol Jennings committed suicide in front of the courthouse.

News of her death spread fast. I saw the aftermath on the evening news—police lights, the courthouse steps cordoned off with yellow tape.

She set herself on fire—a most tragic way to die.

It shocked the entire city. For days, people argued online—some blamed her, others blamed the parents, and a few, like me, just sat in stunned silence, unsure what to think.

I heard that in the flames, she kept crying, “My son is innocent. Why won’t you believe him?”

That echo haunted me. I found myself replaying her words over and over, late at night when I couldn’t sleep.

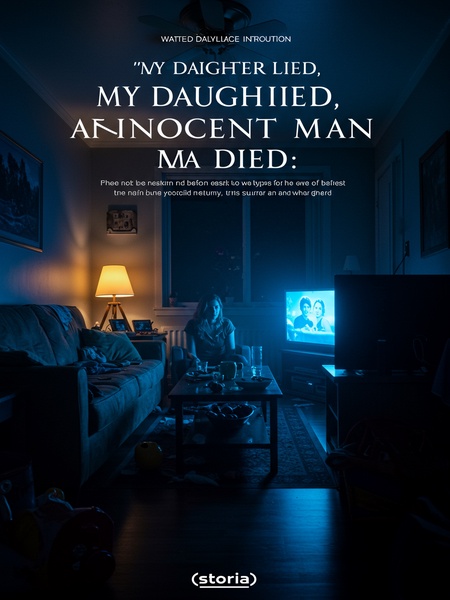

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters