Chapter 1: The River Took My Brother

On the first day of the New Year, my elder cousin, Chijioke, left behind ₦7 million in high-interest debt and jumped into the river to end his own life.

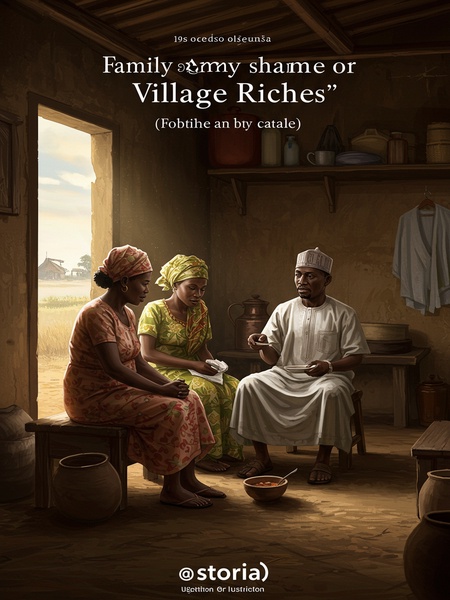

The weight of that news pressed on my chest like harmattan dust after rainfall—clinging, suffocating, sharp. Even as the village drummers beat their agogo in celebration that morning, our compound sat in silence, cold and heavy. Even the fowl wey dey make noise for morning keep quiet, like say dem sabi wetin happen. News like that, e no dey waste time fly. Women wey dey fry akara for the junction dropped their spoons, mouths wide, as if they just heard masquerade voice in broad daylight. One even drop her frying spoon, whisper, “Abomination don land o!” The kind grief wey enter our family that day, na only God fit understand.

My uncle told me some villagers had called Chijioke out to play cards. Not only did he lose all the money he’d hustled for the whole year, he even ended up owing money with wicked interest rates.

Omo, that night, my uncle voice just dey shake like generator wey get bad plug. He say: 'Dem call your cousin go play, dem do am ojoro. Money just vanish, next thing na debt. The kind interest dey bite pass fire.' I picture Chijioke sitting for that smoky corridor, palm-slap on thigh, chasing small luck, not knowing na wolves dey circle am. For this village, card game get two face: one for fun, the other fit finish man.

The creditor called my uncle, threatening him: if he didn’t get the money ready by tomorrow, they would come and seize his house. My uncle, with no other choice, came to beg me for help.

I see the worry for my uncle face—eyes red, shoulders hunched like person wey sleep on plank. The way our people dey value house, e be like shrine. To hear say house go go because of card debt—e weak everybody. Neighbours dey peep through raffia fence, whispering, making sign of the cross. Nobody wan collect wahala. My uncle come kneel down for my front: 'Biko, my pikin, help us.' If you no help, our family name go spoil finish.

I told him, "Uncle, abeg go house first. Tomorrow, I go handle am."

I give am that assurance, pat am for back, even though my mind dey race. Sweat dey my palm, but for face, I gats strong. For my spirit, I dey vow: nobody go disgrace our family so.

After my uncle left, I called my younger cousin, who just came back to the village a few days ago. He sighed heavily:

He sounded tired—like person wey carry block from morning reach night. He fit no too old, but trouble don age am. I hear the background noise: goats bleating, children dey shout for compound. Na village evening be that.

"Me self no too clear for the matter. But I fit bet say na Musa Okoye and him boys set am up. That Musa Okoye family na proper street boys. If not so, how dem take get money build house for city, build big compound for town, dey drive Range Rover dey do show? No be all this their card game wey dem dey use collect villagers money every New Year?"

His suspicion carry the weight of old grudges, the type wey dey run through family gossip. Everybody sabi Musa Okoye matter—how dem dey run things for back, how dem dey shine teeth for front. In our place, if you see man dey build two-storey house, people go dey whisper: 'No be card money?'

I don dey hear this kind thing for years. Every year, young people wey come back from hustle go play cards, dem go use trick collect all their savings. After New Year, everybody go go back to hustle. The thing just dey repeat every year.

Every festive period, e be like script. Boys wey carry bag come from Lagos, from Onitsha, go gather. One shout go enter air, beer go flow, cards go land table. Before cock crow, two or three people go dey find money to transport go back city. Mama Nkechi for market go talk: 'New Year don chop another person.'

Chijioke, over fifty, na proper village man. Him dey manage life, save every kobo from the work wey e dey do outside. Every year, him go carry the money come back, dey plan to build house and help him nephew marry wife.

He be the kind man wey dey use cutlass clear farm by himself, body full of sun, but heart gentle. If he dey talk, children go dey listen. People dey respect am because e no dey do gra-gra, e dey plan for future, dey help as e fit. Every year, na so he go count bundle of notes, tie with rubber band, keep for corner of his wooden box.

So how e take reach like this? How e take gamble away all the money, borrow with killer interest, then on top everything, jump enter river kill himself? No matter how I reason am, e no just add up.

I dey remember how he go say, 'No worry, small small, everything go set.' For man like that to just reach breaking point? My chest dey tight. Na so life dey quick turn for this side?

I press my younger cousin for gist, but he say him no know anything.

He just dey shake head, avoid my eye. For village, if you dey ask question wey fit bring wahala, people go dodge you. As e hang up, I hear him wife voice in background: 'No put mouth, abeg.'

I call some other people for village, but all of them dey dodge, tell me make I go ask Musa Okoye direct.

Everybody suddenly turn deaf and dumb. If matter reach Musa Okoye, people dey fear. Nobody wan carry another person load. Even the ones wey dey form close, na so dem go say, 'Ah, my brother, I no dey that place.'

My mama and papa die when I still small. Na this my cousin hustle pay my school fees for secondary and university. Even when I buy house for city, na him still support me with money. I still remember the day he sell him last goat just to send me transport fare.

I no fit forget. He be like father for me. The time I dey run go write WAEC for nearby town, na him give me transport. The first time I get fever for university, na him wire me money. I get reason to fight this matter, no be small.

Even though we be the same generation, age gap reach twenty years. I dey see am like papa most times.

If wahala reach our family, na him first go face am. He fit call me 'my pikin' in front of elders. My respect for am no be here.

Now, just like that, he don go. E leave wife and pikin, my old uncle, plus ₦7 million debt with interest wey dey run one percent every day.

The debt dey gather like bushfire wey wind dey blow. Wife just dey cry, pikin dey ask, 'Mama, when Papa go come?' My uncle dey look ceiling, eyes red. For village, if you owe like this, your name fit enter meeting list. Shame na heavy cloth.

As I dey look the picture my uncle send—Chijioke body, swollen and pale, as dem drag am commot from river—I just bite my teeth, knock wall hard:

My phone screen almost fall for ground as I dey look the thing. I close my eye, hiss, pain dey burn my throat. I swear by my papa grave, this thing no go end like that.

"I must hear from Musa Okoye mouth."

I carry the pain like black stone for chest. For this life, silence no dey solve problem. Even if e go cost me, I go pursue the matter reach the root.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters